Seeking Relief From Drought, Navajo Turn to NASA

Credit: Pixabay / Pexels.

The horses came from miles around. Seeking life, they found death.

Last spring, the arid western edge of the Navajo Nation in Arizona was drier than it had been in many years. Feral and wild horses, dehydrated and malnourished, sought out a watering hole near Gray Mountain. Instead of finding relief, nearly 200 got stuck in muddy clay and perished.

It’s a scene that comes to mind for Carlee McClellan when he thinks about drought.

On the Navajo Nation, access to drinking water is limited, more than 40 percent of homes lack running water, and many people haul water over 50 miles by truck to replenish their storage cisterns. But if we want to understand what water, rain and drought mean there, we need to think beyond household use.

Drought has a huge impact on agriculture, threatening the survival of plants and animals alike. McClellan grew up on the reservation with his grandmother, practicing traditional dry farming, which relies on rainfall instead of irrigation and involves a variety of techniques for conserving scarce moisture. So he knows how reliant his people are on crops and livestock like horses, cows and sheep.

“Crops and livestock are an integral part of Navajo life,” said McClellan. “Water is important on many different levels beyond what you have coming into your home.”

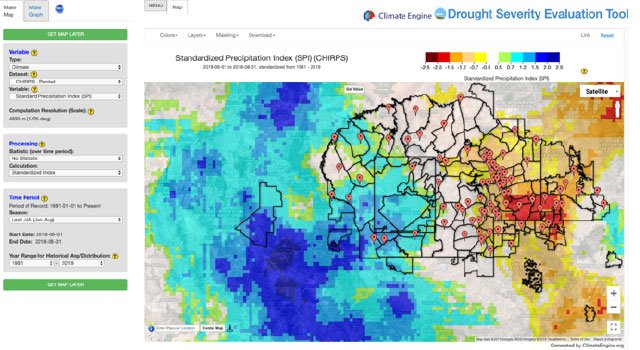

Those many levels explain why McClellan, senior hydrologist for the Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources, is committed to developing the Drought Severity Evaluation Tool. The tool – a collaboration between NASA’s Western Water Applications Office (WWAO), the Navajo Nation and the Desert Research Institute – is geared to helping the Navajo improve its ability to monitor and report drought. It combines precipitation data from NASA satellites, drought indices and on-the-ground rain measurements within a user-friendly web application.

Managing the water resources of the Navajo Nation is particularly difficult. With a population of over 200,000, it is the largest federally-recognized sovereign tribe in the U.S. in land area, located in the four corners region of the southwestern U.S. The Nation experiences frequent and pervasive droughts, with very variable precipitation patterns amid a backdrop of consistently rising temperatures. Declarations of drought emergencies such as the one made in 2018 are common, when millions of drought-relief dollars were used to mitigate the issue.

Ralphus Begay (left) and Irving Brady (center), with the Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources, take monthly precipitation totals at a rain-gauge location. The NASA Ames Research Center team, including former team member Rachel Green (right), visited multiple locations to better understand the ground-based sampling approach. Credit: Amber McCullum.

While the technical capabilities of the tool are important, equally important is the approach to building relationships that has been taken by the NASA team involved. These relationships are critical to building the capacity of the Navajo Nation and ensuring the science can be put to use. McClellan was impressed by the tenacity of the interns responsible for the prototype (put together as part of NASA’s DEVELOP program), including Vickie Ly, now a University of Washington graduate student, who volunteered many hours to working out glitches. He is similarly impressed by the commitment of his current partners at the NASA Ames Research Center in California – project lead Amber McCullum and project advisor Cindy Schmidt – to designing a tool that can meet his department’s unique needs.

Dr. Amber McCullum, lead for NASA WWAO’s Navajo Nation Drought Project.

As a research scientist, McCullum is keenly aware of the assumptions her profession often makes about what communities need from science. “There’s this ‘if-we-build-it-they-will-come’ mentality,” she said. “Scientists often think ‘we have these great tools and all these new models for you.’ But then the tools end up never being used.”

The drought project has taken a different approach. “It’s more a case of ‘what are your needs and what do you want the tool to do?’” said McClellan. When McCullum poses these questions to him, McClellan sometimes feels like he asks for too much. But he says she and the NASA team consistently respond with creativity and optimism.

“To my surprise, NASA keeps coming back with more creative solutions and possibilities,” McClellan said. “I’m thoroughly impressed with the options. They’re exceeding my expectations.”

That’s how WWAO believes the work needs to be done. WWAO starts by asking water end-users and decision makers what they would most need to make better-informed water decisions. Then it builds projects and applications that apply NASA’s data and expertise to meet those needs. “The most important aspects of these projects are the partner involved and the iterative process,” Amber McCullum said.

Artist’s rendering of NASA’s Global Precipitation Measurement core satellite orbiting Earth. Credit: NASA.

Putting science to work

Looking down at the Earth from space, WWAO taps extensive satellite data from the Climate Hazards group InfraRed Precipitation with Stations data (CHIRPS), the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission, and the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) to understand just how dry things have become with shifting water patterns across the west. As communities like the Navajo Nation change, NASA hopes that its Earth observation data can change things for the better.

By June 2020, the Drought Severity Evaluation Tool is scheduled to be deployed. McClellan and McCullum are enthusiastic about the difference this Navajo Nation / NASA partnership will make.

When the Navajo Nation declares a drought emergency, area-specific data could be used to distribute relief funds. Currently, funds are divided evenly among the Nation’s 110 chapters, analogous to U.S. counties. But some chapters, especially in western areas, have less water and a greater need for funds. The Drought Severity Evaluation Tool will enable regional differences to be quantified, and acted upon.

It will also generate reports and maps on the fly, showing precipitation for a specific chapter over the last 60 days, for example. Having such detailed, accurate, and current analyses will help officials and managers make more informed decisions not only in distributing relief funds but also in planning for the future. McCullum and McClellan foresee the tool being used in drought mitigation, decision making about streamflow diversions, and design and management of water-related infrastructure such as reservoirs, as well as in restoration efforts.

“We’re spearheading a number of different watershed restoration projects,” said McClellan. The tool will allow the Navajo Nation team to evaluate precipitation in a given watershed across any timespan. We want to be able to hone in on drought severity and needs in various areas.”

The future of Earth science

Both partners hope their collaboration is a sign of things to come.

The Drought Severity Evaluation Tool showing the Navajo Nation boundaries and the 85 rain-gauge locations. This map displays the CHIRPS-generated Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) values from June to August 2018. The data underscore the variability of the SPI across the Nation, particularly during the monsoon season. Source: Drought Severity Evaluation Tool.

For her part, McCullum wants to get scientists thinking about research in a more real-world, applicable way. “There’s often a big disconnect between hardcore research and the people making decisions,” she said. “From the beginning, we need to build relationships and work with people who will use the tools.”

McCullum also hopes the project makes decision makers in state and local governments more aware of how remote-sensing data can be used. “A project like this that’s so engaged with the people who benefit can provide an example for other organizations,” she said. “There’s a wealth of data out there. The question is how to organize and use it effectively.”

At his desk in Fort Defiance, Arizona, McClellan hopes this will be a catalyst for other projects. He is eager to work with NASA’s Airborne Snow Observatory, for example, to understand snowpack and snowmelt across the Navajo Nation’s mountain ranges.

He also hopes to see NASA working with other teams focused on natural resources, such as the Navajo Department of Agriculture. Land managers might not be able to prevent the kind of tragedy that occurred near Gray Mountain last spring, but a tool designed specifically for their work in this unique place could help them assess forage cover and strike a healthy balance between the land’s capacity to produce vegetation and the demands upon it from extensive grazing by livestock, wildlife, and feral horses.

“It could help us keep a better balance,” McClellan said.